PART I: Worlds Apart

Chapter 1- Kham: Village Life and Shedra

“Om Mani Padme Hung, Om Mani Padme Hung, Om Mani Padme Hung…” He awoke to the sounds of mantras whispered on the breath of his parents as they carried about their morning ritual before the sunrise. His mother, a petite Tibetan woman with plaited gray hair and a compassionate nature, stoked the fire while one of his older sisters churned the butter tea in the tall, thin wooden urn. The fire crackled and popped, the suction sounds of the tea urn kept a rhythmic beat, the smell of thick smoke and earthy incense filled his lungs. The only light in the dark one room home was emitted by the butterlamps on the shrine and the skylight from above the earthen stove that let the smoke out from the house. His older brothers and sisters were starting to stir, woken, too, by the sounds and smells of the making of butter tea. Soon, all eleven of them would be enjoying their breakfast of tsampa, roasted barley flour that is the staple of the Tibetan diet, and salted butter tea in their wooden cups. They would sip in silence, rubbing their eyes, and then lick the wet surface of the tsampa, holding their cups out to their mother to be filled again. They would continue like this until their cups were empty and their stomachs full. The sun was up and work on the farm was to be done.

As the youngest member of the family, Tsering was exempt from work on the family farm. It had been decided at his birth that he was to become a monk. His mother, Yangchen, gave birth to him, her eleventh child, when she was fifty years old. None of her other children had been given to the monastery or nunnery. So knowing this would probably be her last child, she and her three husbands decided to put the family’s honor in this baby’s hands. His youngest father, Dhondrup, had been a monk before the Chinese occupation. He, like so many other young members of the ordained Sangha, had been forced by the Chinese to leave the monastery and lead the life of a lay person. Dhondrup joined his brothers’ household and became Yangchen’s third and youngest husband. It was custom for brothers to live together and take one woman to share as a wife. This rare practice of polyandry was the tradition in their region of Tibet. It was a practical way to keep the family wealth intact and avoid arguments over inheritance and division of land throughout the generations. Together the three brothers and Yangchen raised all eleven of their children, with no concern over whose child belonged to whom. Since Dhondrup had spent many years as a monk he was the one member of the family who was literate. When Tsering was born Dhondrop decided to pass on this skill, knowing that Tsering would need to read the holy scriptures when he entered monastery.

As the older brothers and sisters left the house with bags on their backs full of provisions for the day, Tsering stayed back with Pa Dhondrup to be home-schooled. Although none of the children knew which one of their three fathers was their actual biological father, Ama Yangchen was the only member of the family who ever knew this truth, Tsering looked the most like Pa Dhondrop. They both had a crook in their nose and the same skinny frame. Despite their slight build they were both deceivingly strong. They were also the youngest of their siblings, or Chungwas. When Tsering started to learn to read, Pa Dhondrup would have him recite his Ka-Kha-Ga-Nga, the Tibetan alphabet, with much speed and gusto, almost to the point of screaming it at the top of his lungs. His father would then take down and carefully unfold one of the family’s scriptures, a volume from the Kangyur, the complete collection of the teachings of the Buddha, that was housed above the family’s shrine. He set it on a hand-made and painted table designed specifically for this purpose and would read the text out loud as his son tried to follow along. Tsering was a bright boy and at five years of age was able to read well enough to know when to turn the long, rectangular unbound pages for his father. By the time he turned ten he was being invited by the local villagers to read the scriptures out loud as a blessing for their homes and families. In this way Tsering was able to generate merit for himself and as well as those who had sponsored his prayers.

One of Tsering’s greatest accomplishments during these early years was reading the complete 108-volume collection of scriptures called the Kangyur, the words of the Buddha. Each volume has around 300-400 pages each and it took Tsering more than one year to accomplish this task. This was Tsering’s gift to his family as it is custom for Tibetan Buddhist families to have their homes blessed by the recitation of this sacred text.

When Pa Dhondrop had business to tend to on the farm, Tsering would enjoy his freedom and go exploring the mountains that surrounded their village. Yarunka, as their village was named, was built on the slope of a mountain. It overlooked a beautiful valley through which a large river ran. Sixteen families shared the mountainside together and communally cultivated the land with crops of barley, turnips, and droma, a small root vegetable much like a miniature sweet potato that is a Tibetan specialty. Since the village had been built on the mountainside the homes were built into the slope of the earth. This helped insulate the homes in the long cold winters and cool them in the summers. The homes were built from the timber pines and red earth by the families themselves. The homes looked as though they grew out of the earth itself. The villagers were completely self-sufficient, weaving their own rugs from the wool of their own sheep, building their own furniture from the pines cut down in the forest, and harvesting and cooking the food that they planted in their fields. They rarely had need to make the day’s trip to the county market where they would trade for a few staples like salt, sugar and tea.

When Pa Dhondrop had business to tend to on the farm, Tsering would enjoy his freedom and go exploring the mountains that surrounded their village. Yarunka, as their village was named, was built on the slope of a mountain. It overlooked a beautiful valley through which a large river ran. Sixteen families shared the mountainside together and communally cultivated the land with crops of barley, turnips, and droma, a small root vegetable much like a miniature sweet potato that is a Tibetan specialty. Since the village had been built on the mountainside the homes were built into the slope of the earth. This helped insulate the homes in the long cold winters and cool them in the summers. The homes were built from the timber pines and red earth by the families themselves. The homes looked as though they grew out of the earth itself. The villagers were completely self-sufficient, weaving their own rugs from the wool of their own sheep, building their own furniture from the pines cut down in the forest, and harvesting and cooking the food that they planted in their fields. They rarely had need to make the day’s trip to the county market where they would trade for a few staples like salt, sugar and tea.

Tsering’s family’s herds roamed the lush mountaintops in the summer months. They owned over one hundred yak and thirty goats, using their milk to produce butter, yogurt and cheese. In the summer months, their animals fattened on the abundant green mountain grasses, herbs and wild flowers. It was said that the yaks of Riwoche county were the largest, healthiest and strongest in all of Tibet. The traditional Tibetan diet was simple, one completely dependant on the staples of barley, yak meat and dairy products that derived from the milk of the dri, the female companion to the yak. In the winter months the family would bring the herds down into the valley where they provided them food and shelter until the spring came. It was a semi-nomadic lifestyle where the adults and children alike followed the cycles of the seasons and their precious animals that provided them sustenance.

Tsering’s family’s herds roamed the lush mountaintops in the summer months. They owned over one hundred yak and thirty goats, using their milk to produce butter, yogurt and cheese. In the summer months, their animals fattened on the abundant green mountain grasses, herbs and wild flowers. It was said that the yaks of Riwoche county were the largest, healthiest and strongest in all of Tibet. The traditional Tibetan diet was simple, one completely dependant on the staples of barley, yak meat and dairy products that derived from the milk of the dri, the female companion to the yak. In the winter months the family would bring the herds down into the valley where they provided them food and shelter until the spring came. It was a semi-nomadic lifestyle where the adults and children alike followed the cycles of the seasons and their precious animals that provided them sustenance.

The villagers’ respect for the local deities was so strong that they made offerings to them annually with the help of the lamas from the monastery. Together the lay people and monks would go to the mountain top on foot or on horseback, climbing through forests of giant rhododendrons which were inhabited by monkeys. Once they arrived past the tree line at the barren mountaintop they would make offerings of prayer, fire and ritual. Into the fire they offered juniper which grew in abundance on the mountainside. The smoke billowed into the sky and filled the air with intensely fragrant white clouds. The usual silence was broken with the rhythmic sounds of brass cymbals and bells, the beating of drums and the low chanting of the monks and lamas. These rituals were done according to tradition that had been passed down for centuries. The specific date was determined by the local astrological expert. Each village sent representatives to the mountaintop on the specified day of the year to carry prayers, respect and offerings to the deities. In return, they believed the deities would protect their crops and livestock from harm, disease, or natural disaster.

Up on the mountaintop the weather was unpredictable. Within just a few moments the sunny warm skies of July could change to blustery dark clouds that rained hail or showered snow. The villagers were hardy folk, however, and these sudden changes in the weather were no hardship for them. These mountains were Tsering’s playground. He knew every peak and valley for a good ten mile radius like the back of his hand. Sometimes he would bring his dog Jeri with him as a companion on one of his mountain adventures. Jeri was a Tibetan mastiff, a large long-haired mountain dog that helped to herd the family’s yak and warned the family when wolves or fox were a threat. Jeri was a handsome dog, his fur was amber colored and Tsering loved him dearly. Tsering loved all the animals on the farm, especially the yak. He took great pride in the health and size of his family’s herd.

When Tsering was around five years old, his family took a pilgrimage to the holy city of Lhasa. Everyone sat in the back of a cargo truck during the six day journey west on dirt roads across the rugged landscape of Tibet. Over mountain passes and through beautiful valleys, they chanted mantras, sang, told stories and jokes while bouncing along over the bumpy roads. When they arrived in Lhasa they went to the Jokhang Temple where they made offerings of butter to the many butterlamps, juniper and cedar as smoke offerings, and prostrations before entering inside to see the most sacred of Tibetan statues, the Jowo Yibshin Norbu, a giant statue of the Buddha in Sambogakaya form. Tibetans from all of the country make pilgrimage to Lhasa to be blessed by this statue. They offered katags, white ceremonial scarves, and money, making aspirations for peace and well-being of all. When back outside the family enjoyed circumambulating the temple together while browsing the many vendors’ stalls along the circuit of the Barkhor. The elders spun their hand-held prayer wheels and counted mantras on their mala beads. It is while the family was making their circumambulations that Tsering had his first encounter with a Westerner. Tsering’s mother, Ma Yangchen, took notice of a Western tourist and brought Tsering’s attention to the strange-looking foreigner. “Shatsa,” Ma Yangchen said, “So cute,” looking towards the tall, brown-haired lady with very white skin. Tsering looked at her in awe, wide-eyed and mouth gaping open. The lady noticed him and attracted by this cute little boy with a shaved head, dressed in a sheep-skin chuba (a traditional Tibetan robe), she couldn’t resist picking him up in her arms. Tsering was both shocked and shy to be in the arms of this strange-looking foreigner but his family all laughed and took much pleasure in this unusual encounter with an “Inji” or foreigner.

At the age of fifteen Tsering learned the art of tangkha painting from a cousin. He started learning this sacred skill by drawing many hands and feet of the Buddhas. Once he had mastered this skill he moved on to drawing the face with it’s slightly opened eyes and subtle knowing glimpse of a smile in the lips. His hand was steady and his long, slender fingers had a natural grace that lent themselves perfectly to the delicate art of tangkha drawing. Next, his cousin instructed him in the geometric precision of thiktsa in which the proportions of the Buddhas’ bodies must never disobey. In this way Tsering learned the mathematic disciplines of arithmetic and geometry. Now that he had mastered line drawing he was introduced to color mixing and application. His cousin showed him how to make glue or gesso from rabbit’s skin and mix it with natural minerals like iron and cobalt to produce brilliant colors. He made his own paint brushes using the hair from cats. It was always a challenge to sneak up on the cats and manage to pull out a few hairs at a time victoriously. The lines of the tangkhas needed to be extremely fine so not many hairs were necessary to make the finest brushes. He also learned how to stretch and tie the cloth of the tangkha onto a wooden frame using rope in a zig zag formation.

Now that he had all the requisite skills he was ready to invite his first deity onto the cloth. He chose to start with Guru Rinpoche, the patron saint of Tibet who brought Buddhism from India to the Snowland of the Himalayas. His family was devout Nyingmapa, practitioners of the ancient school, who are known for their zealous faith in Guru Rinpoche. His first tangkha was going to be not just one but a series because Guru Rinpoche had eight manifestations. He knew that he would master tangkha painting if he committed himself to such an ongoing project. It took him just under a year to complete the series, each tangkha took him about one month to complete. His family proudly displayed each completed tangkha on the walls of the family shrine after they had been blessed and consecrated by the Lama of the county monastery.

Now that he had all the requisite skills he was ready to invite his first deity onto the cloth. He chose to start with Guru Rinpoche, the patron saint of Tibet who brought Buddhism from India to the Snowland of the Himalayas. His family was devout Nyingmapa, practitioners of the ancient school, who are known for their zealous faith in Guru Rinpoche. His first tangkha was going to be not just one but a series because Guru Rinpoche had eight manifestations. He knew that he would master tangkha painting if he committed himself to such an ongoing project. It took him just under a year to complete the series, each tangkha took him about one month to complete. His family proudly displayed each completed tangkha on the walls of the family shrine after they had been blessed and consecrated by the Lama of the county monastery.

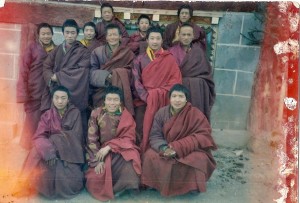

His family invited the Lamas and monks of Riwoche Gonpa to their home annually to perform a Drupchen, or great accumulation of merit, in which ten days of intense, around- the-clock prayer and ritual was performed in the family’s name and dedicated to all sentient beings. The family cooked and hosted the twenty or so Lamas and monks in their home for the duration of the ceremony, serving them three meals and tea continuously throughout the day. It was one of the most exciting times of year for Tsering. He became friends with the younger monks and participated in the ceremony with them to his best capacity. He was especially fond of the Tulku, or reincarnate lama, who sat on the throne, presiding over the ritual. The Tulku took a special liking to Tsering as well, advising the family that soon he would be ready to enter monastery.

His family invited the Lamas and monks of Riwoche Gonpa to their home annually to perform a Drupchen, or great accumulation of merit, in which ten days of intense, around- the-clock prayer and ritual was performed in the family’s name and dedicated to all sentient beings. The family cooked and hosted the twenty or so Lamas and monks in their home for the duration of the ceremony, serving them three meals and tea continuously throughout the day. It was one of the most exciting times of year for Tsering. He became friends with the younger monks and participated in the ceremony with them to his best capacity. He was especially fond of the Tulku, or reincarnate lama, who sat on the throne, presiding over the ritual. The Tulku took a special liking to Tsering as well, advising the family that soon he would be ready to enter monastery.

Unlike many other boys like him, though, his family was reluctant to send him away. They of course knew the great merit to be accumulated in his entering monastery, but they were so fond of his presence. It was not until he was eighteen years of age that his family decided he should leave home. It was decided by a local Lama that he should travel out of Riwoche and go to Shedra, or monastic university, in the neighboring county of Nangchen. With a supply of yak meat, tsampa, dried cheese, and butter, Tsering left home alone for the first time. Many tears were shed by all as he left the comfort and security of a home full of love. Ama Yangchen wept as she said goodbye to her youngest child. Tsering’s eyes welled with tears as he promised to pray for her long life and their swift reunion. The entire village saw him off, each offering him a white katag, a traditional silk scarf with auspicious symbols woven into it, as a wish for a safe journey and a safe return. After a bumpy three day drive in the back carriage of a truck across several mountain passes, Tsering was grateful to arrive. He was introduced to the resident Khenpo, or Abbot, of the monastic community and entered the renowned Dzogsar Shedra in Dege.

It was a huge change from the easy lifestyle back home. Although his fathers had instilled a strong sense of discipline and study in him, he had no way of expecting the strict regime of Shedra. Every morning the monks were awoken by a gong at five AM. The monks stayed enclosed in their rooms for early morning study for two hours. The second gong of the day was the signal that they were free to leave the confines of their rooms. This was the time for the student monks to ask for clarification on the material being studied that day to the senior monks. At eight o’clock the community broke for breakfast. After breakfast the gates to the college were opened and the monks seized the opportunity to relieve themselves. At nine o’clock they entered the main hall of the temple for teachings by the resident Khenpo. Khenpo would read and comment on a section of scripture each day and in the afternoon the monks would have to then read these pages of scriptures individually, understanding their content and memorizing their stanzas to their best capacity. The next day Khenpo would call on any one of the several hundred student monks to come in front of the monastic community and tell what they had remembered and understood, quoting from the scripture as much as possible. This would all be done without the help of notes or the scripture itself. It was all to be from memory. Needless to say, it was always a very anxious moment when the Khenpo would randomly draw a name everyday. Tsering devoted himself to his studies everyday, spending six to eight hours reading, contemplating and memorizing. In this way he was sure to be spared the embarrassment of being called upon with nothing to say.

In the three years that he lived at Shedra he was called upon several times. Although he loathed public speaking and struggled with keeping his voice loud and steady (he had a nervous habit of clearing his throat every few seconds when speaking before a large group), he was gifted at grasping the poetic and academic language of the scriptures and memorizing their stanzas. He soon became known in the community for his talents. There was one occasion, however, when Tsering found himself called upon when he was not sufficiently prepared. When Khenpo called his name he asked to be excused from speaking, explaining that he was feeling under the weather. Khenpo accepted his excuse and Tsering was grateful to have been spared that day.

During his time at Shedra, Tsering developed a strong friendship with a young Khenpo named Lobsang Dongyal. Lobsang’s family was local and Tsering was often invited to spend scholastic breaks with Khenpo’s family since his own home was so far away. Just before his final year at Dzongsar Shedra, Khenpo Lobsang was asked to teach at another monastery. Because they shared such an affinity for each other, Khenpo asked Tsering to come there with him. Tsering accepted and continued his studies under him. Soon Khenpo grew ill and had to return home to convalesce. He asked Tsering to take over his teaching duties and in this way Tsering started his first post as a teacher. He stayed there for a year. At the end of the year commitment, Tsering went to stay at Khenpos’ family home again. When Khenpo was in good health the friends decided to make a pilgrimage to the sacred capital city Lhasa together. There they would seek out the famous Khenchen Torutsenam and request to study Sanskrit and poetry under him.

This is so engaging, Jess! I’m loving reading it. You write so well, & the story is fascinating. Can’t wait for the next chapters. Thanks for sharing it. You are an inspiration!!

Thank you for your heartfelt support and encouragement, Liz! I’m having fun sharing it!

I love it — want to read more.

Awesome, Carla. It’s good to have you backing me up!

Thank you for this peek into Tibetan life.

You’re more than welcome, Michelle! Thanks for sharing the journey with me!

I love the part about the making the glue, paint, and paintbrushes!

Thank you so much for sharing your writing! I am looking forward to devouring all of it! Beautifully written…

Thanks for reading and commenting, Maureen. I appreciate your support! I’m glad you found my blog!