Chapter 3- Lhasa: Sanskrit and Poetry

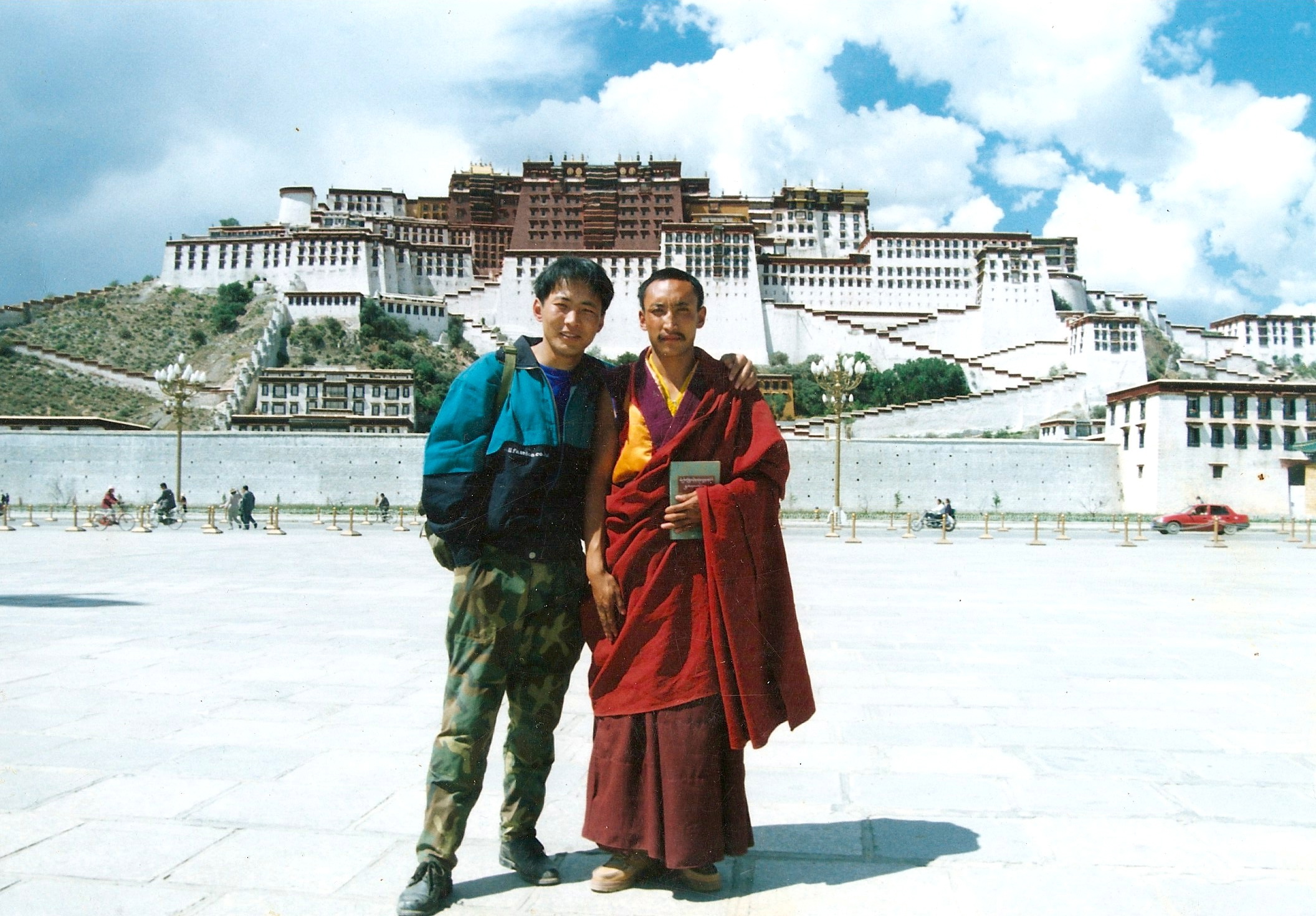

When the two young monks arrived in Lhasa the first thing they needed to do was find a room for rent. Luckily, Khenpo Lobsang’s brother had a contact who owned a two-room apartment for rent for only 200 Yuan a month, the equivalent of 20 dollars a month. Once they settled in they spent their first days visiting the holy temples and pilgrimage circuit of Lhasa: the Potala Palace, once the Dalai Lama’s residence and now a museum run by the Chinese government, the Jokhang Temple which houses Tibet’s most revered statue of the Buddha, the Norbulingkha– the Dalai Lama’s summer palace which now attracts tourists with a zoo, and the ever-crowded Barkhor that encircles the Jokhang temple and serves simultaneously as a circumambulation route for pilgrims and a marketplace for Tibetan vendors.

When the two young monks arrived in Lhasa the first thing they needed to do was find a room for rent. Luckily, Khenpo Lobsang’s brother had a contact who owned a two-room apartment for rent for only 200 Yuan a month, the equivalent of 20 dollars a month. Once they settled in they spent their first days visiting the holy temples and pilgrimage circuit of Lhasa: the Potala Palace, once the Dalai Lama’s residence and now a museum run by the Chinese government, the Jokhang Temple which houses Tibet’s most revered statue of the Buddha, the Norbulingkha– the Dalai Lama’s summer palace which now attracts tourists with a zoo, and the ever-crowded Barkhor that encircles the Jokhang temple and serves simultaneously as a circumambulation route for pilgrims and a marketplace for Tibetan vendors.

It was an exciting time for the young friends- Lhasa was full of pilgrims from all three regions of Tibet: Kham, Amdo and Utsang. Pilgrims came to Lhasa dressed in their finest chubas—Tibetan robes that vary in style by region. They came as families, elders assisted by their grandchildren and babies strapped to the backs of their mothers. Sometimes they came by truck, filling the cargo bed with over fifty pilgrims at a time. Other times they came by horse, riding on beautifully hand-made carpets over the saddle. They also came by foot, wearing thick leather aprons and wooden paddles on their hands to protect themselves as they lay their bodies prostrate on the road the entire journey-long as a physical form of prayer, devotion, and purification. Their foreheads were perpetually sullied by dirt from the constant contact with the earthen roads.

Tsering and Khenpo Lobsang sometimes had a little trouble communicating or bartering with fellow countrymen who did not come from their native Kham, especially the ones who were from Amdo. The Lhasa dialect was not too challenging, they just had to remember to use Shey-sa, the polite level of speech that was reserved back home in Kham for speaking with the Rinpoches, high-ranking Lamas who had reincarnated for the benefit of all beings. Here in Lhasa everyone used Shey-sa with everyone else, unlike Kham where speech was much more casual. The Amdo dialect often presented more difficulty as it used an alternative set of vocabulary and terms. No matter, though, there were enough Khampas in Lhasa to help when needed. Neither of the monks spoke Chinese but this was not a problem because at that time the Tibetan population was still in the majority and they rarely had to communicate with any of the Han Chinese immigrants who lived in Lhasa. All of their needs at the market were met by the Tibetan merchants.

However, one day while the two monks were taking a walk through the center of the city, they had a rather unsettling incident with a Chinese soldier. As they crossed the Kuru Zampa Bridge, Khenpo Lobang took out a Tibetan map of the city. There was a Chinese soldier on duty who asked Khenpo to show him the map. The Chinese soldier could not read Tibetan and grew suspicious of the monks. He asked the monks their purpose but neither of them could speak Chinese and were unable to answer the guard’s questions. The soldier quickly grew impatient and angry with them and kicked Khenpo several times in the knees. Tsering tried to protect his teacher and friend by holding back the guard but this made the guard even more violent. He took the machine gun off his back and pointed it at the monks while screaming at them in Chinese. Tsering quickly released and jumped away from the guard and stood there in shocked silence. The conflict was soon resolved when a Tibetan soldier arrived on the scene and was able to mediate and translate for the two parties. This incident had a profound impact on Tsering’s outlook on the Chinese occupiers with whom he shared his homeland. He realized how important a skill it was to learn the Chinese language so as to avoid conflicts like this one in the future.

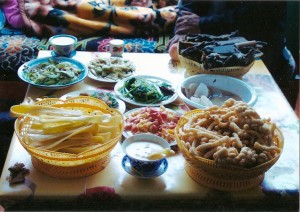

Khenpo and Tsering enjoyed their days off visiting the homes of family and friends who lived in Lhasa. There was much gossip and storytelling to catch up on as their city kin was always curious to know how life was going on back in the hometown villages. The monks were always well fed by their cousins as well, sipping endless cups of hot butter tea and feasting on traditional Tibetan foods like steamed dumplings, dried yak meat, and droma (the Tibetan equivalent of sweet potatoes that are miniature in size, boiled and served in melted butter and sprinkled with sugar.)

Khenpo and Tsering enjoyed their days off visiting the homes of family and friends who lived in Lhasa. There was much gossip and storytelling to catch up on as their city kin was always curious to know how life was going on back in the hometown villages. The monks were always well fed by their cousins as well, sipping endless cups of hot butter tea and feasting on traditional Tibetan foods like steamed dumplings, dried yak meat, and droma (the Tibetan equivalent of sweet potatoes that are miniature in size, boiled and served in melted butter and sprinkled with sugar.)

The monks did not waste much time before seeking out the renowned teacher Torutsenam, their main reason for coming to Lhasa. Torutsenam was known as Tibet’s most qualified living scholar of Sanskrit, the ancient language of the Buddhist scriptures. Upon their first meeting they requested Torutsenam to accept them as his students but he told the young monks he did not have time to take them on because he was too busy. However, he suggested that they ask one of his advanced students to teach them. He gave each monk a copy of his book to study and gave them a basic introduction to the reading and writing of the Sanskrit alphabet. They started their studies with Norbu Tashi who met with them everyday for two hours. They continued their studies with Norbu Tashi for six months until they completed the text that Torutsenam had given them.

The monks also pursued the study of poetry at this time with a teacher named Khen Tsewang who taught them the thirty-five ornaments or poetic devices used in the traditional art of Tibetan poetry. They used an historical anthology called “Dendri Gongyen” or “Ornament of Yugpachen’s View” written by Bodkhe in 1678 as their main text. As Tibetan poetry is based on Indian poetry, the collection of poems by the famous Indian poet Lobpon Yugpachen called “Melongma” or “Great Mirror” were included in their Tibetan translations of Bodkhe’s text. Everyday Khen Tsewang would analyze specific stanzas with his students, discussing the different poetic devices used by the poet. He would then ask his students to return home and write an original poem using the same devices and style to show him for critique the next day. Tsering enjoyed his study of poetry immensely and quickly developed a habit of writing poetry on every scrap piece of paper he could find.

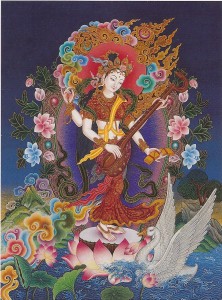

Life in Lhasa for the two young monks was peaceful and productive; their friendship inspired each other to greater heights of scholarship and fraternity. At the end of the six month study of Torutsenam’s Sanskrit text, Norbu Tashi gave the two monks a small graduation ceremony in which they were given new names. Tsering received the name Tsangse Mawe Dhonjo which relates to Yangchenma or Vajra Sarasvati, the Tibetan Buddhist female deity of arts and education. The Sarasvati was once a great Indian river that has since dried up. It is still revered today by tantric practitioners as an invisible symbol of the union of the subtle male and female energies of the central channel. Having accomplished their goal the two monks returned to their homeland in the eastern region of Tibet called Kham. Tsering’s family was so proud and happy to receive him home after so many years away. Though they wished he would stay, they accepted that his destiny would soon call him elsewhere. And so it did. Soon enough, Tsering decided to travel back to Lhasa on his own to continue his studies of Sanskrit. But his karma was soon to lead him even further from home, much further. The naming after Sarasvati was a harbinger of things to come.

Life in Lhasa for the two young monks was peaceful and productive; their friendship inspired each other to greater heights of scholarship and fraternity. At the end of the six month study of Torutsenam’s Sanskrit text, Norbu Tashi gave the two monks a small graduation ceremony in which they were given new names. Tsering received the name Tsangse Mawe Dhonjo which relates to Yangchenma or Vajra Sarasvati, the Tibetan Buddhist female deity of arts and education. The Sarasvati was once a great Indian river that has since dried up. It is still revered today by tantric practitioners as an invisible symbol of the union of the subtle male and female energies of the central channel. Having accomplished their goal the two monks returned to their homeland in the eastern region of Tibet called Kham. Tsering’s family was so proud and happy to receive him home after so many years away. Though they wished he would stay, they accepted that his destiny would soon call him elsewhere. And so it did. Soon enough, Tsering decided to travel back to Lhasa on his own to continue his studies of Sanskrit. But his karma was soon to lead him even further from home, much further. The naming after Sarasvati was a harbinger of things to come.